The Dragon's Head Blog: Notes on Anatomy and Physiology: One Big Tendon

In an earlier article, it was mentioned that we are often asked in class to open Tiger’s Mouth, bring fingertips up, drop elbow, turn wrist or send out the hands. Why is that? What role do the upper limbs play in learning our art? How do they contribute to the balance and strength of our overall structure?

Go back to our discussions about the thoracolumbar fascia and tensegrity as you think about this. We saw then that stretching out the body’s web of soft tissue grants both structure and power. For a sense of this, imagine a clothes line drawn taut, a balloon inflated to stretch out its walls, or guy ropes and poles adjusted to establish the right amount of tension in the fabric of a tent. In each instance, the separation of individual elements provides coherence of form to the whole structure and stores elastic recoil energy in the process.

We’ve looked at how Tiger’s Mouth opens the soft tissues, joints and arches of the hand. This stretching of elastic elements provides the hand with increased strength of structure. And furnishes the brain with the sensory input needed to help locate not only the hand but also the regions with which the hand eventually connects – chest, spine, pelvis and feet.

The same thing happens when the hands go out from the torso. By elongating the ties that bind the various elements of the upper limb, or connect the upper limb with the rest of the body, structure is created. One end of the elastic stretches out from the other.

As we shall see, this involves the shortening of some muscles and their tendons so that others may lengthen. The complexity of human movement, mind you, warrants that the elements which contract and those which elongate shift from moment to moment. What is important is that there are always lines of pull.

To get an idea of the tissues that are either elongating or contracting as we make use of our upper limbs, it is useful to learn a bit about some of the muscle groups in the forearm and arm. Enough to appreciate that many individual muscles, their tendons, sheets of connective tissue (fascia), nerves, blood and lymphatic vessels work together to establish a line of pull. To create what Master Moy sometimes called one big tendon. The goal is not to review the detailed anatomy of individual muscles but to gain insight into how groups of muscles work together as an integrated whole.

When describing the concept of one big tendon, western health practitioners sometimes employ the term myofascial meridians (myo = muscle, fascia = connective tissue). Both terms chronicle the lines of force that run from muscle to tendon to fascia to bone, transmitting tension and movement across the entire fibrous web of the human form. Recently, Thomas Myers came up with the expression Anatomy Trains to describe this phenomenon.

So, let’s briefly examine several muscle groups of the upper limb, starting with those that flex and extend the wrist and ending with the elbow flexors and extensors. Recall that flexion involves bending a joint to bring the bones closer together while extension straightens or opens the joint. To be brief, I will necessarily render simple what is extraordinarily complex. In real life, any given muscle is capable of carrying out multiple tasks, depending on what the other muscles in the region are doing.

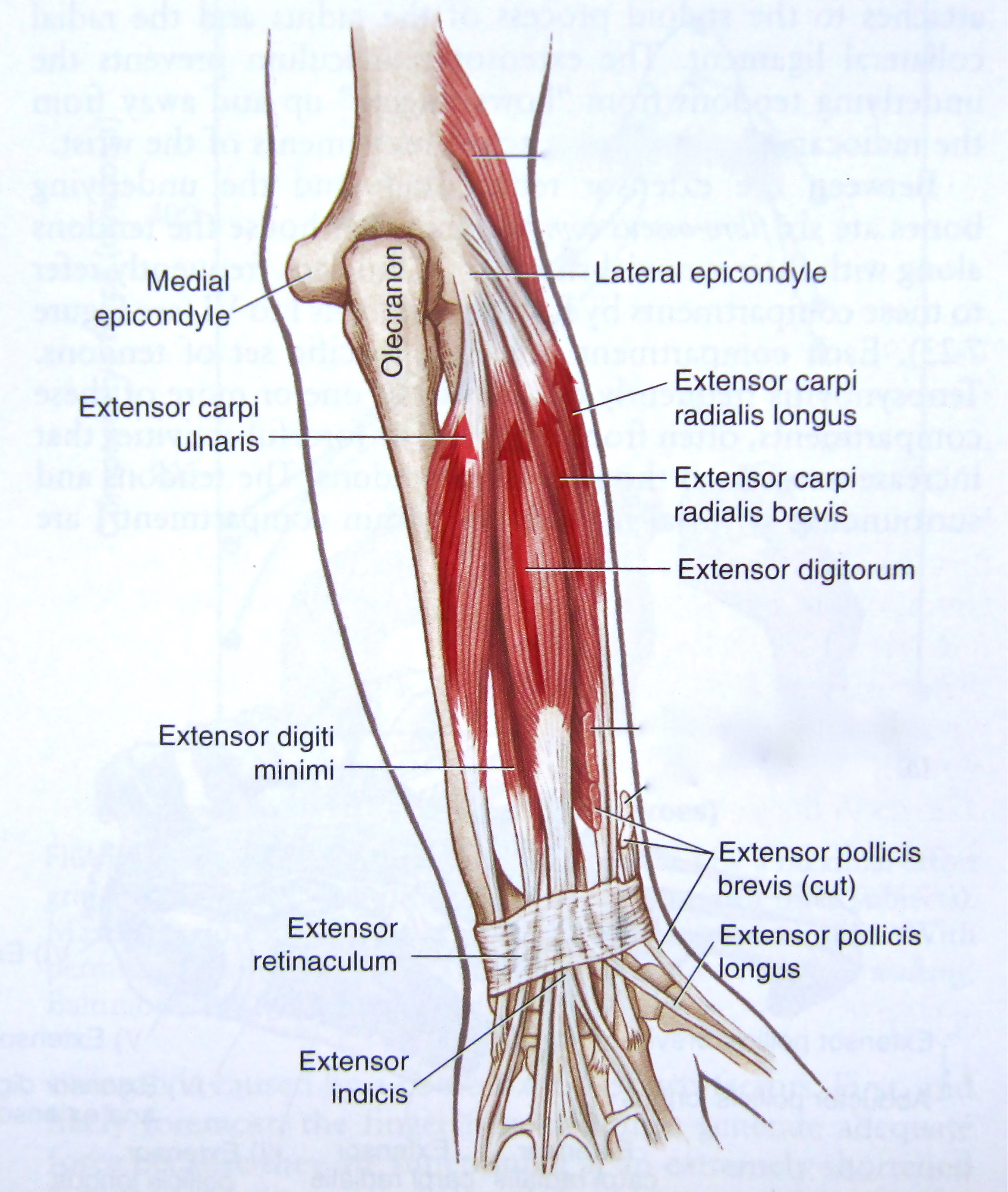

The wrist extensors

When we send out the hands in the tor yu with fingertips up, we are extending both wrist and fingers. A leash of closely packed muscles are used to do this, muscles which start out together at the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, flow as a group down the back of the forearm, cross the wrist under a fibrous band (retinaculum) and attach to various bones in the hand. The muscle bellies give the upper outer forearm much of its bulk. The forearm tapers as muscle gives way to tendon.

Simply lift the fingertips and hand and this entire complex is activated as one.

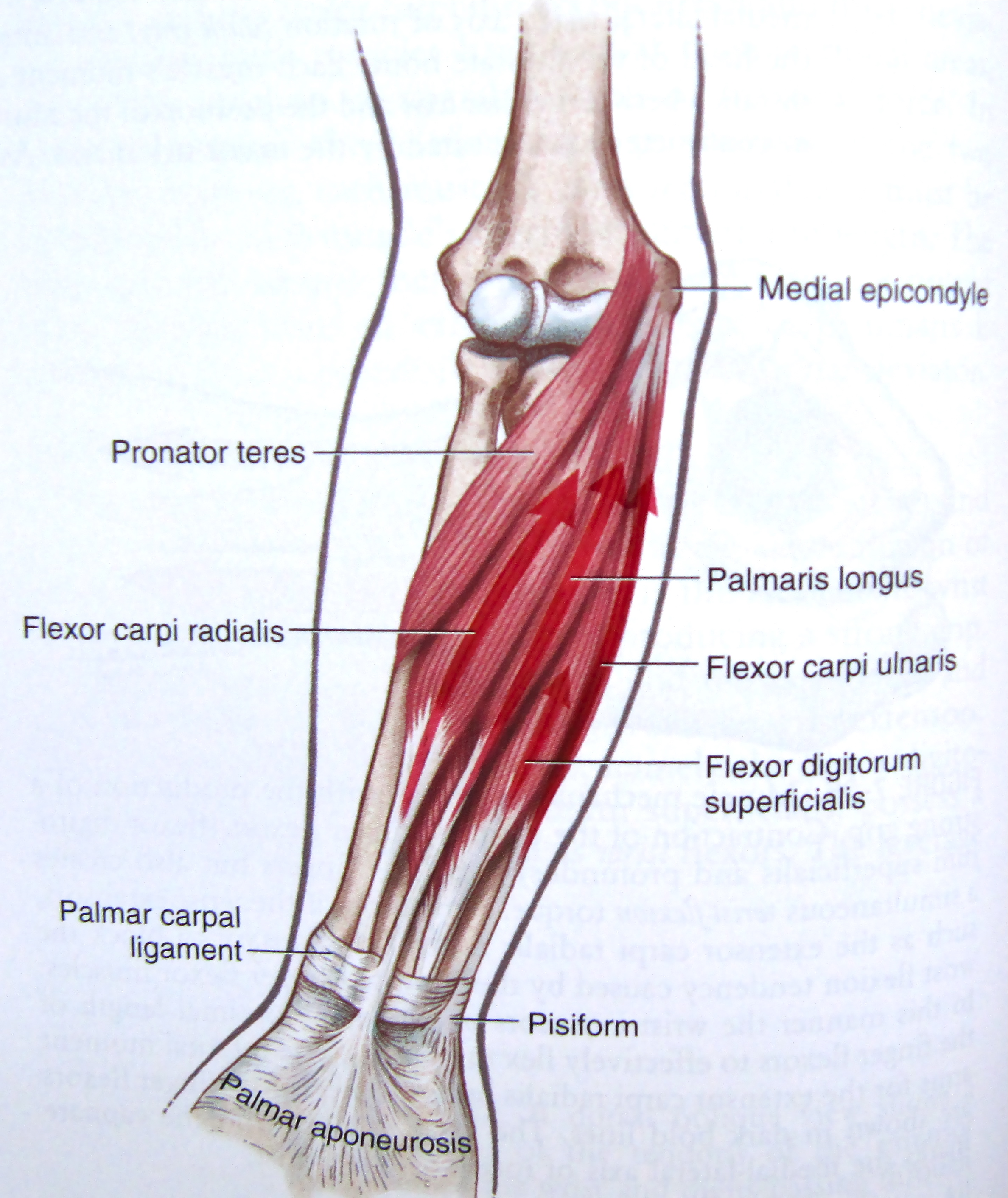

The wrist flexors

With the right hand forming a beak at the end of Whip To One Side or the bottom hand in Wave Hands Like Clouds, the wrist and fingers are flexed. Once again this is accomplished by a collection of muscles which, this time, take off from the inside aspect of the humerus at the medial epicondyle. As these muscles run down the front to the wrist and hand, they fill out the upper inner side of the forearm.

Contract the wrist flexors and the tissues running along the back surface of the hand, wrist and forearm are lengthened and drawn taut. Extend the wrist and fingers and we establish a line of pull along the front surface of the palm and forearm. Wrist flexors and extensors, called antagonists because of their opposite actions, are actually working side by side. One group lengthening, the other contracting to engage continuities that bind segments of the body to one another. Yin and yang creating a whole.

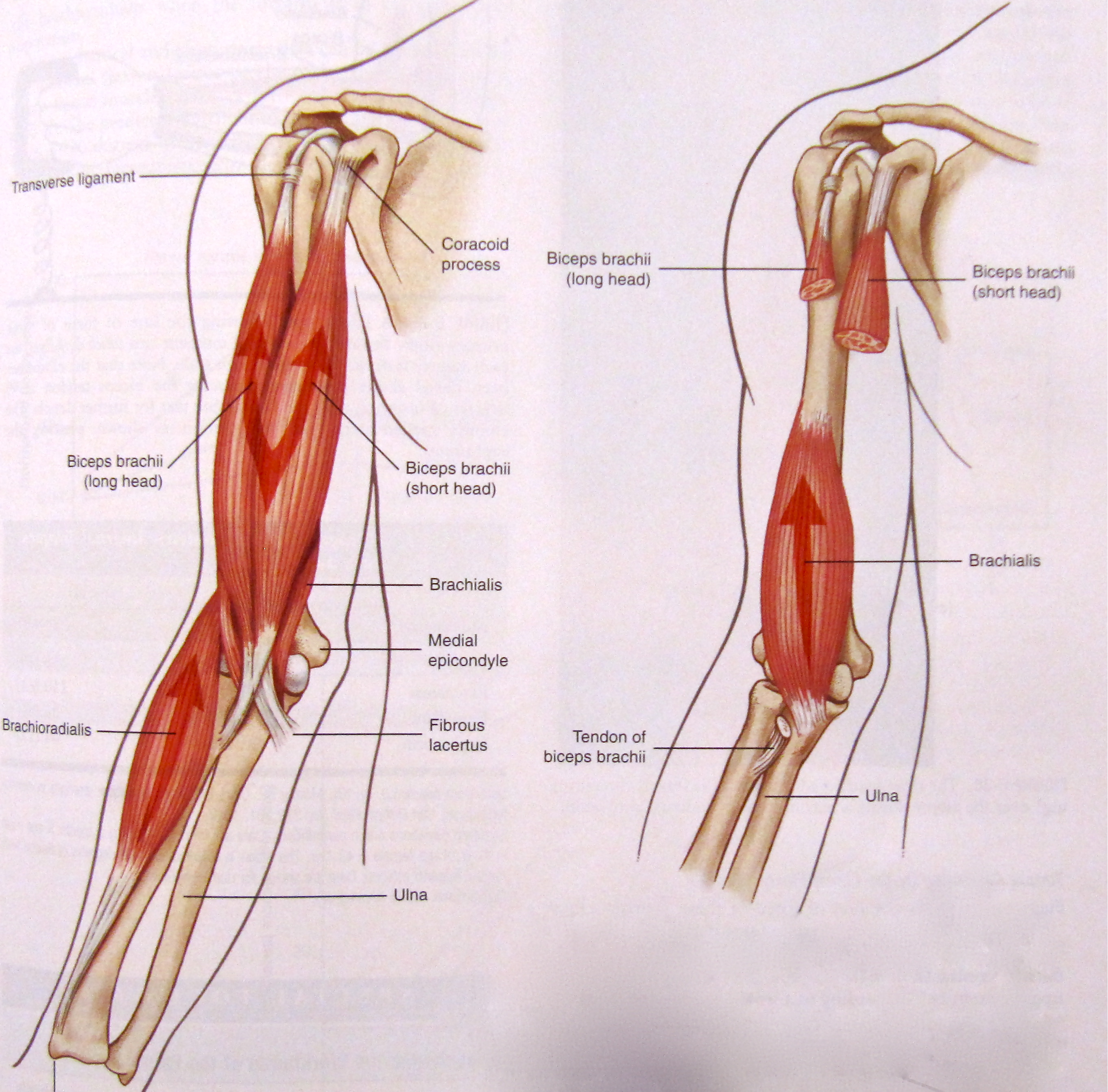

The elbow flexors

When we come back in the tor yu or hold the ball anywhere in the set, the muscles that flex the elbow and draw the hand toward the shoulder are activated. These muscles include the biceps, the brachialis and the brachioradialis.

The biceps has long and short heads, the tendons of which attach to different points on the shoulder blade. Its bottom end hooks into the radius and, by means of a fibrous cord called the fibrous lacertus, fixes to the ulna as well. That this single muscle with its tendons crosses two major joints (shoulder and elbow) and connects up with three bones (scapula, radius and ulna) illustrates the unifying influence of the myofascia.

The brachialis lies deep to the biceps. The brachioradialis runs from the lower humerus all the way down to the bottom end of the radius.

It’s worth mentioning that the biceps also plays an important role in supination of the forearm – turning the palm toward the face. While practicing the first arm foundation exercise, notice the action of the biceps as the hand turns in. This simple exercise involves more of the upper limb than we initially thought.

The elbow extensors

There are two muscles that straighten the elbow, the triceps and the much smaller anconeus. As the name suggests, the triceps consists of three muscles; the long head runs up to the scapula, and the medial and lateral heads attach to the humerus. The medial head lies deep so is not seen in the left hand image of figure 4.

Extend the elbow in Parting Wild Horse’s Main and you create a line of pull in the soft tissues running along the front of the arm, elbow and forearm. Send out the hand at the same time and that pull is also felt along the back of the arm, down the side of the chest to the sacrum and beyond.

Flex the elbow as you hold the ball or come back in the tor yu and you once again feel a pull along the posterior aspect of the arm and onto the sides of the rib cage.

These movements of the elbow have a strong impact on the structures connecting upper limb with torso – something we will look at more carefully next time.

In review, then, the contraction of particular groups of muscles and their tendons are used to pull on and lengthen other groups. This permits us to move through space while reinforcing our structure as we go. Tiger’s Mouth, lift fingertips, drop elbow, turn wrist, send out hands are the mechanisms by which the upper limbs contribute to structure and power.

Two kinds of strength intertwine. One comes from activating muscle. The other stems from letting go, relaxing, elongating, lengthening our soft tissues.

We begin to appreciate how body wide continuities are unceasingly created and then released as we move. One big tendon in constant flux. Lines of influence that run from finger tips to trunk, down the legs and into the feet. The hands become the tip of a whip, the arms part of its length, and the legs and spine its handle.

1. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System, Foundations for Rehabilitation, Second Edition, 2010, Donald A. Neumann, Mosby Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-323-03989-5