The Dragon's Head Blog: Notes on Anatomy and Physiology: Degenerative Disc Disease

Let’s continue with the examination of intervertebral discs begun in the last post. This will also give us a chance to examine some of the normal changes associated with aging of the spine and to have a look at degenerative disc disease, a difficulty frequently encountered in the lumbar region.

Many mysteries remain about how the spine actually works. But because low back pain is common, the intervertebral discs of the lumbar spine have been extensively studied. One of the things well established is the varying pressure generated within a normal lumbar disc as the spine moves with the activities of daily life. This information helps us think about preventing disc disease and how to avoid aggravating an already established disc injury.

The above chart points out several things of interest to us as practitioners of the Taoist Tai Chi™ arts:

- pressure within the nucleus pulposus is lowest when we lie supine. This is one of the benefits of sleeping meditation.

- pressures are maximal when we carry something in front of the body while bending forward

- whilst sitting or standing, forward bending (flexion) puts greater pressure on the discs than does an upright posture. As we see in figure 2 below, it also invites the disc to bulge posteriorly towards nervous tissue that is very sensitive to pressure. When doing the tor yu or the set, we are asked to first send out the hands and then the whole body (not just head and chest), to keep looking out at eye level, and to settle the weight without tipping forward at the waist. All these instructions discourage forward bending of the lumbar spine, minimize the pressures to which the discs are subjected and allow those with degenerative disc disease to practice safely.

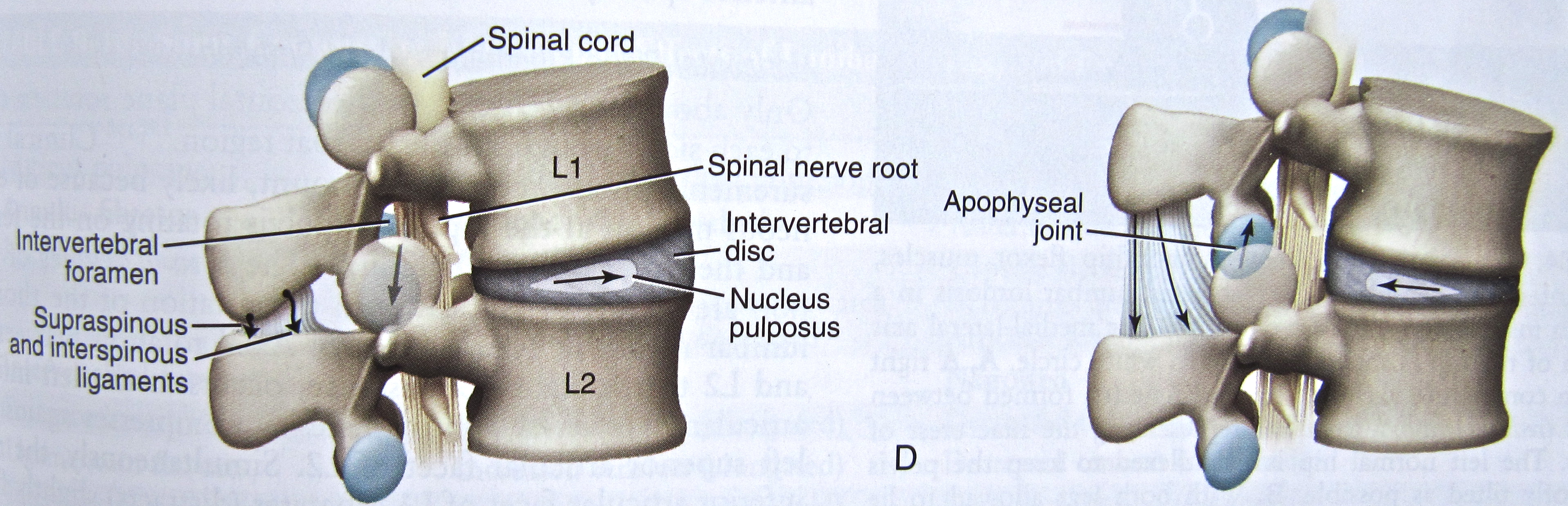

Figure 2 Forward bending with the low back, seen in the image to the right, encourages the disc to migrate towards the tender nervous tissue lying within the spinal canal while opening the facet (apophyseal) joint and intervertebral foramen. Bending backwards (extension), shown in the image to the left, tends to shift the nucleus away from the nervous tissue lying in the canal but closes the facet joint and intervertebral foramen. Neumann, 2010, page 355 Now, what we consider to be normal structure in the spine is certainly altered by disease, trauma, misuse, inactivity and poor posture. But it is also very much influenced by age:

- From infancy to age 10, the always meagre blood flow to the disc diminishes further and the disc begins to adapt to a lifetime of working in conditions of low oxygen (anaerobic metabolism). By early adulthood, biochemical changes occur that cause everyone’s discs to start drying out. With a decline in water-retaining capacity, the discs lose volume and intrinsic pressure, and begin to bulge out when compressed. Think of the shape of a tire that is insufficiently inflated with air. The discs are now less able to cushion the endplates and vertebral bodies from compressive loads.

- The disc’s connective tissue alters with an increase in collagen fibers and a decrease in elastin. The distinction between annulus and nucleus becomes less apparent. A greater share of the vertical load falls to the annulus and tears begin to appear in its rings.

- The endplates become less permeable to nutrients passing from vertebral body to disc.

- The trabecular bone of the vertebrae weakens, leading to a greater reliance on cortical bone for load bearing, and the vertebral bodies become more susceptible to injury.

- Wear and tear appears in the cartilage covering the articular surfaces of the facet joints.

All these degenerative changes form part of aging but are seldom severe enough to cause trouble.

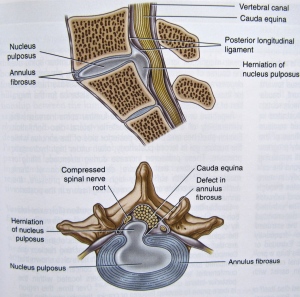

With sufficient damage to a disc, however, herniation may develop and we move from a normal aging process to pathology. This is especially likely to occur in the lumbar spine. The annulus can no longer contain the nucleus and a portion of the latter migrates posteriorly or posterior-laterally. If it drifts far enough, the nuclear material impinges on and injures the delicate nerve tissue normally protected by the spinal column. Commonly, it is one of the nerve roots making up the sciatic nerve (the L3,4 and S1,2 roots) that is affected, producing sciatica – a variable pattern of pain, altered sensation, loss of reflexes and weakness in one leg. The exact symptoms of sciatica are determined by which spinal nerve root is compressed and how severely.

As suggested by the disc pressure studies outlined earlier, people suffering from lumbar disc disease do not like to bend forward. Nor are they comfortable with sitting. Both activities aggravate their disc protrusion and symptoms.

Clearly, the seated set is not meant for people with pain from a bulging lumbar disc. And the forward bend in Push Needle To Sea Bottom and The Opening and Closing of Tai Chi may well need to be abbreviated – as gauged by how those movements feel to the student. Otherwise, as long as bending at the waist is avoided, the 108 moves of the standing set are remarkably safe and allow someone with lumbar disc disease to remain active and build strength, flexibility, endurance and balance despite the trouble with their back.

In the next post, we will consider another back problem encountered in the practice hall, spinal stenosis, a condition with quite different implications for movement.

1. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System, Foundations for Rehabilitation, Second Edition, Donald A. Neumann, 2010, Mosby Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-323-03989-5