The Dragon's Head Blog: Notes on Anatomy and Physiology: Learning with the Hand and Elbow

Taoist Tai Chi® arts introduce a way of moving that is novel for all students. Because the focus is on balance in all its dimensions, we develop over time a newfound sense of comfort and ease as we practice the 108 moves of the set. It feels as if we are learning to move the way a fish swims or a frog jumps – as a coherent whole.

In order to experience this manner of moving in the world, instruction in class often focuses on the upper limbs. We are asked, for example, to open tiger’s mouth, turn the wrist, send out the hands from the body, or drop elbow. Why is it that these particular uses of this part of our anatomy create balance in the overall structure of the body? What is it about the structure of the upper limbs that grants them such an important impact on everything else?

To answer these questions, we will look initially at what is referred to as the elbow-forearm complex and, later on, investigate the lines of attachment that run between the upper limb and the trunk, pelvis and lower limbs.

First, though, it would be useful to become familiar with a few of the anatomical terms used to describe the body and its movements.

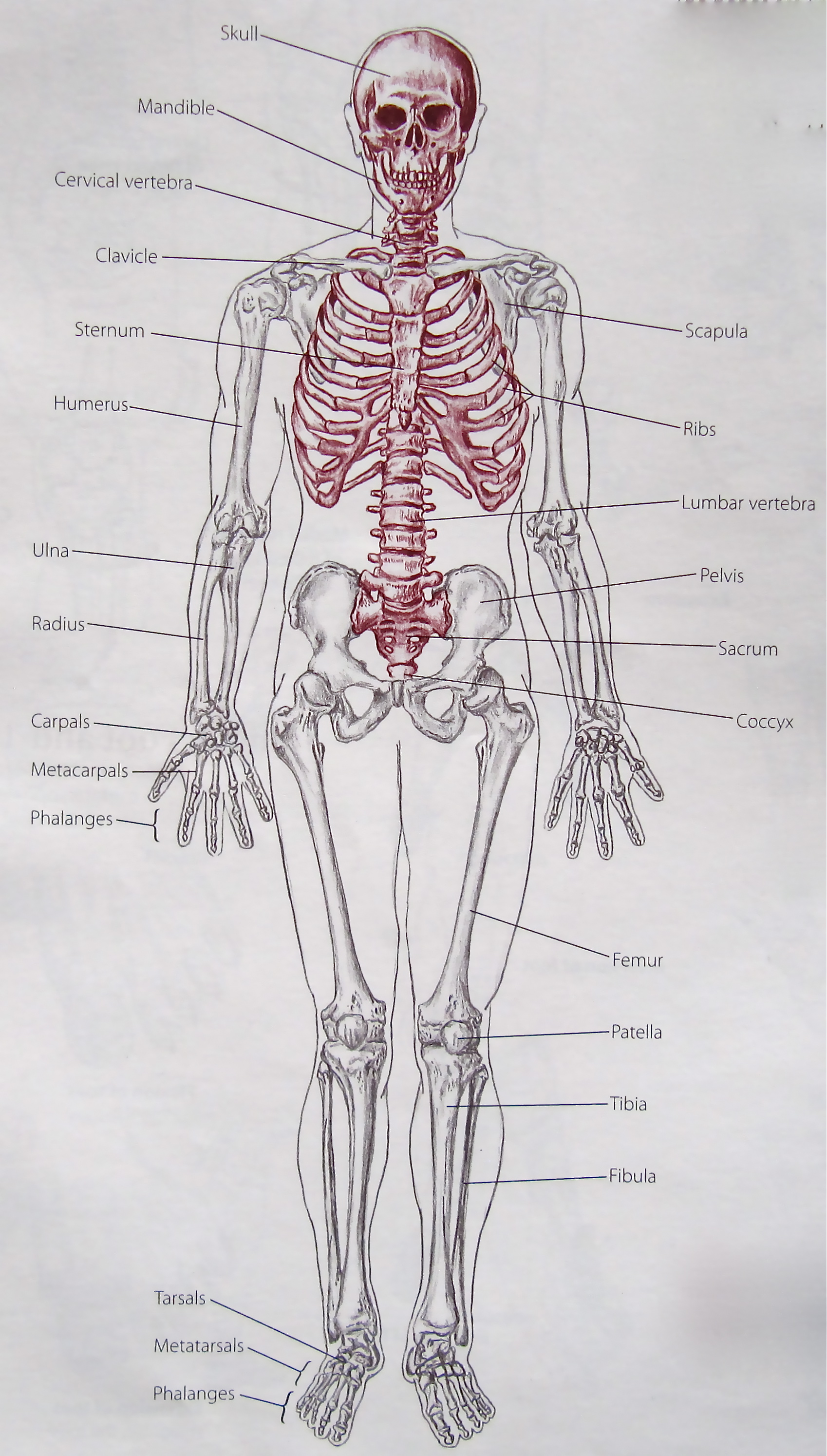

The anatomical position employed in western medicine is depicted in the drawing below:

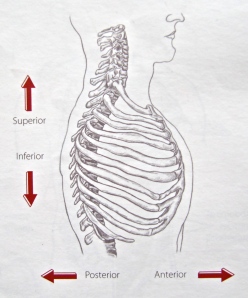

Something lying closer to the head is described as superior or cranial; something closer to the feet is referred to as inferior or caudal. A posterior structure lies toward the back and an anterior one towards the front.

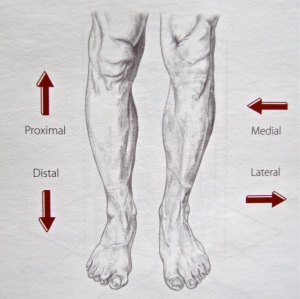

Distal refers to as structure further away from the trunk and proximal describes something closer. Lateral indicates a part further away from the midline of the body and medial a part that is closer.

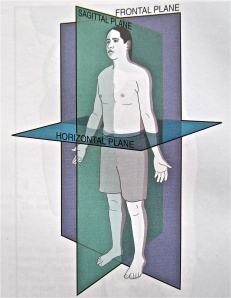

With someone standing in the anatomical position, one can imagine three principal planes running through the body: the sagittal plane which divides the body into left and right halves, the frontal plane which splits the body into front and back portions, and the horizontal plane which separates the body into upper and lower sections. Thinking of these planes helps us describe the movements we make. Movements which may occur in any or all of these planes.

Now, extension is movement that straightens or opens a joint; in the anatomical position, most joints are extended. Flexion, on the other hand, is movement that bends a joint, bringing the bones closer together. Most joints are flexed in the fetal position. Both flexion and extension occur in the sagittal plane.

Abduction carries a limb away from the midline whereas adduction brings a limb towards the middle. Both involve the frontal plane. These terms are used only for the limbs.

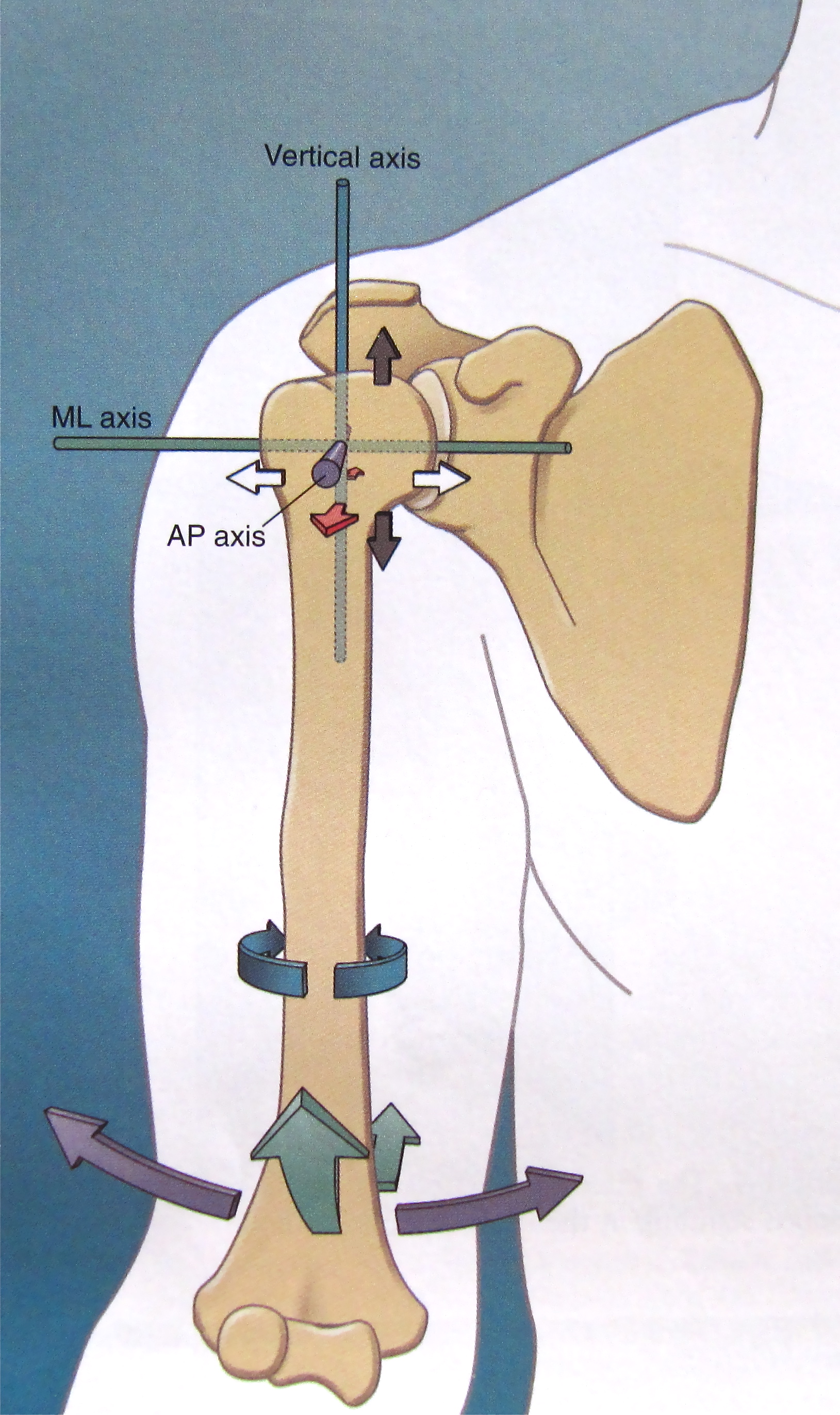

Internal (medial) rotation turns a limb in toward the midline; external (lateral) rotation turns it away form the centre. These movements take place in the horizontal plane. For example, with the quiet opening of the hands at the back of the tor yu, each upper arm (humerus) rotates externally, away from the midline, while the elbows remain in place and pointing downward.

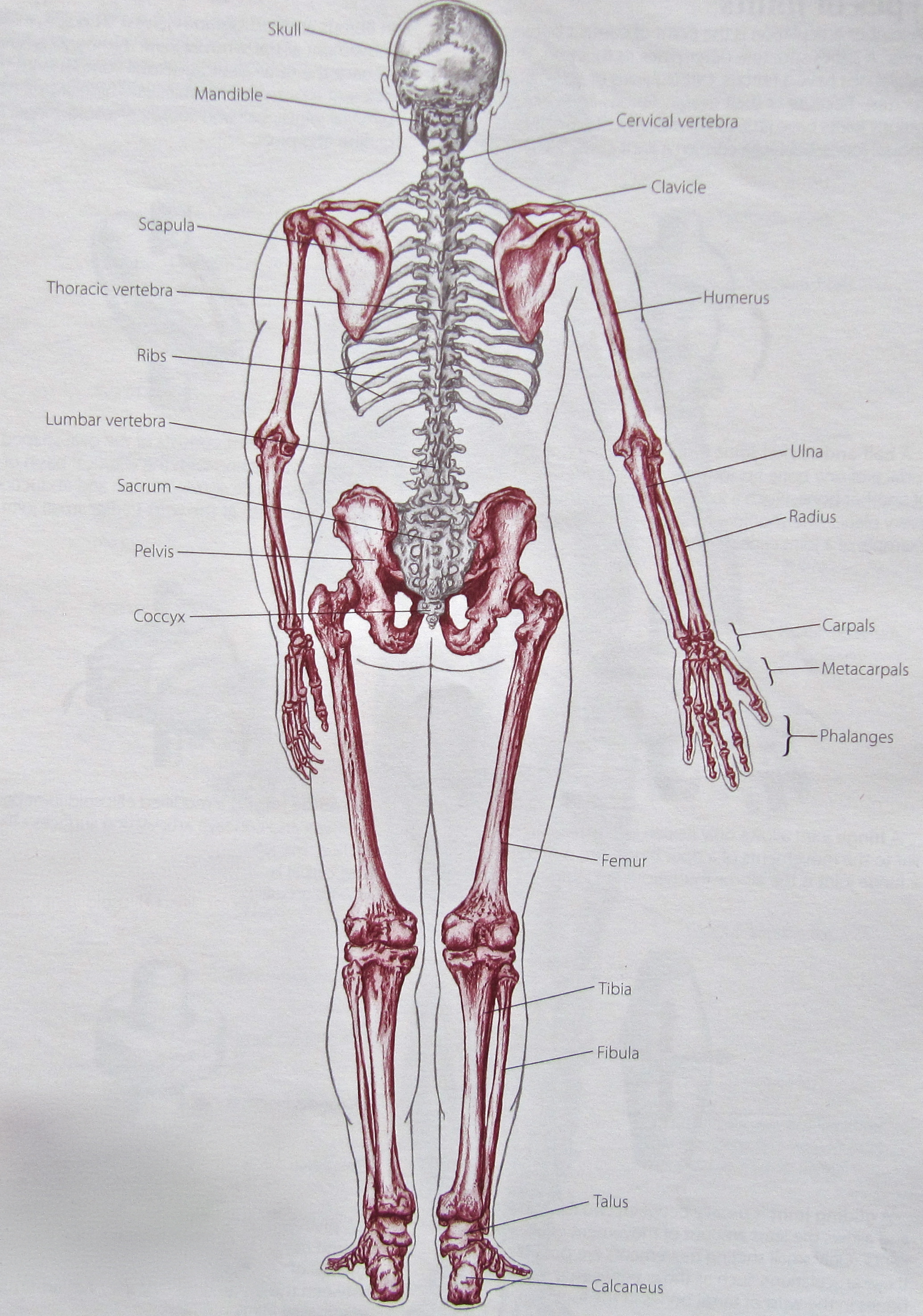

Finally, recall that the upper limbs form part of the appendicular skeleton which is composed of the arms and legs, shoulder girdle (scapulae and clavicles) and pelvic girdle (hip bones).

The axial skeleton, the other major segment of our skeletal system, represents the skeleton’s centre and consists of the skull, spine, sacrum, ribs and sternum. As we examine the links between the upper limbs and the rest of the body, we will see just how entwined these two sections of the skeleton really are. But that’s a topic for another day.

1. Trail Guide to the Body, How to locate muscles, bones and more, 3rd Edition, 2005, Andrew R. Biel, Books of Discovery, ISBN: 0-9658534-5-4

2. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System, Foundations for Rehabilitation, 2nd Edition, 2010, Donald A. Neumann, Mosby Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-323-03989-5