The Dragon's Head Blog: Notes on Anatomy and Physiology: Spinal Stenosis

Our most recent discussion concerned degenerative disc disease in the lumbar spine, a problem common to modern-day humans.

Given the many moving parts that make up the spine, it is not surprising that there are a number of causes for low back and leg pain. The spinal cord and its meningeal wrappings, the vertebrae themselves, the facet joints, and the ligaments, muscle, tendon and fascia that drape about the spine are all possible sources of mischief and discomfort.

Spinal stenosis causes pain that may seem similar to that of lumbar disc disease. But it affects posture and movement in very different ways. We’ll see that these dissimilarities necessarily alter our focus as we teach the Taoist Tai Chi™ arts.

The differing patterns of illness are always instructive. Encountering them

invites us to consider the uniqueness of each person’s situation. One size does not fit all. Each person is dealing with a singular set of circumstances. Both the instructor and the student seek to understand where that particular student is now and how she might best move forward.

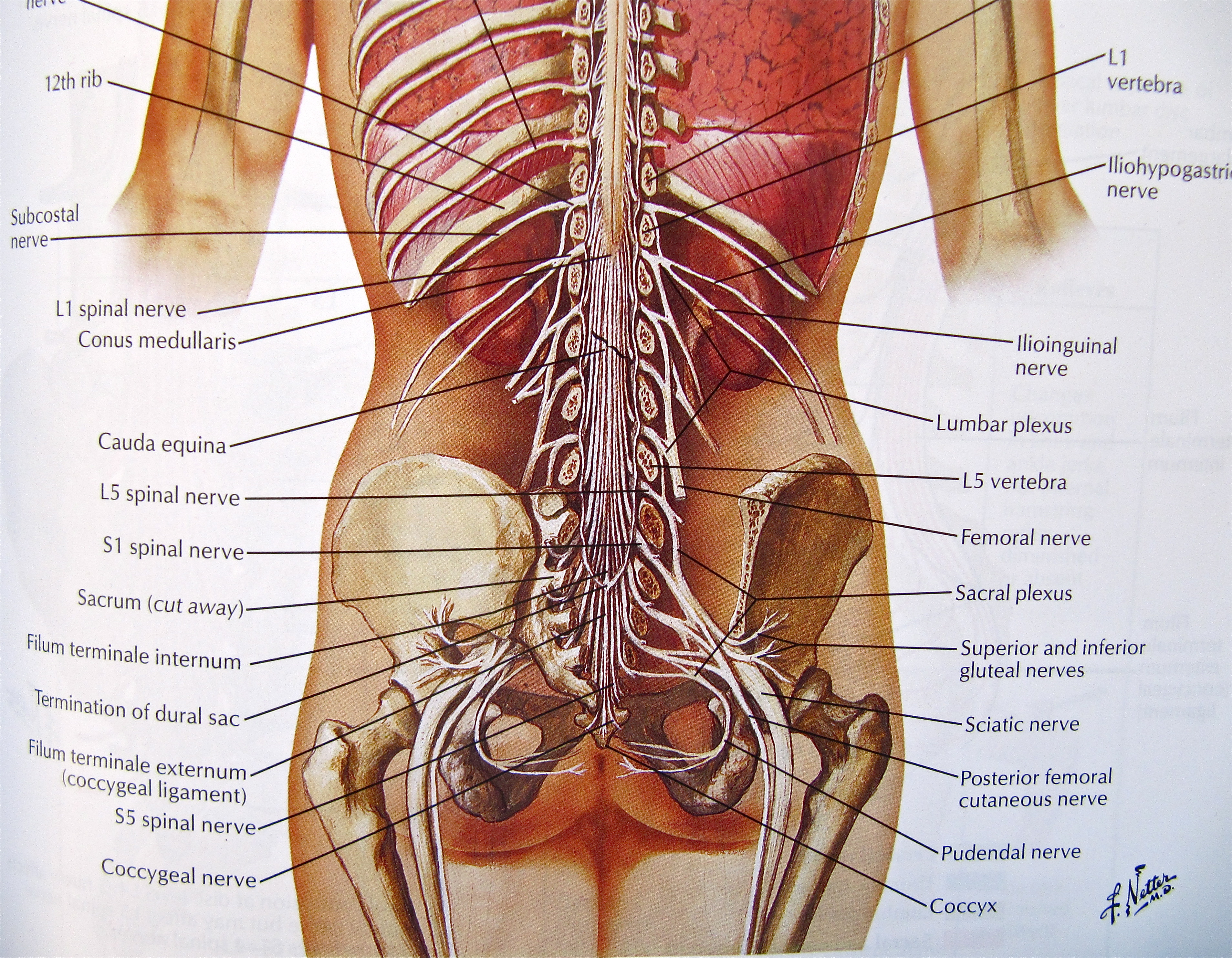

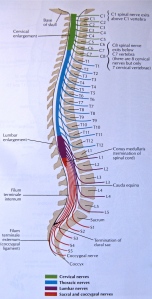

The adult spinal cord is much shorter than the vertebral column. It actually ends at the first lumbar vertebra (L1) where it divides to form the lumbar and sacral nerve roots. These run some distance down the portion of the vertebral canal formed by the lumbar and sacral vertebrae before exiting at the appropriate intervertebral foramen. As they descend the canal, they form a leash of nerves known as the cauda equina or horse’s tail.

As you read through these posts, remember that clicking on any image will render it larger.

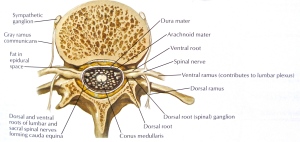

There must be sufficient space in the spinal canal to make room for the nerve roots that form the cauda equina. And the intervertebral foramina have to be spacious enough to not interfere with the roots as they exit the spine. Spinal stenosis occurs when there is a constriction of the spinal canal or intervertebral foramina. Usually both areas are involved in the narrowing.

Spinal stenosis typically appears in people over the age of 60 – much later in life than disc disease normally first presents. The stenosis comes from degenerative changes in the structures that form the boundaries of the canal and foramina. Intervertebral discs herniate into the canal and compress nerve roots. Progressive disc deterioration narrows the gap between vertebral bodies, shortening the spine and decreasing the overall space within the spinal canal. Bony spurs (osteophytes) form at the vertebral bodies or facet joints and push into the canal. The ligamentum flavum that runs along the posterior aspect of the spinal canal thickens and buckles inward. The facet joints narrow from wear and tear arthritis, collapse onto one another and further reduce the volume of the spinal canal and foramina.

These changes usually occur at multiple levels of the lumbar spine. They contract the space in which the nerve roots lie, crowding both the nerves and their blood supply. This leads primarily to pain in the back and legs. It may also result in pins and needles and weakness in the legs.

What is striking about spinal stenosis, when compared to disc disease, is that the pain builds with walking or standing upright, and settles with sitting or forward bending. The reasons for this become clear when we appreciate that an erect or extended posture of the spine narrows the lumbar canal and intervertebral foramina in all of us by:

- approximating the rings of bony arches that attach to the backs of the vertebral bodies

- relaxing and buckling inward the ligamentum flavum that covers the back wall of the spinal canal

- closing the facet joints which overlap like shingles on a roof.

Conversely, full forward flexion of the lumbar spine enlarges the space inside the spinal canal and increases the diameter of the intervertebral foramina by 19% when compared to a neutral upright position.

With the spinal canal and foramina already constricted by spinal stenosis, the additional narrowing produced by an upright posture brings on pain and the person adopts a forward stooped posture.

Let’s take another look at an image first introduced in our discussion of lumbar disc disease:

So, unlike people with chronic disc disease, students with spinal stenosis want to bend forward at the waist and may have great difficulty standing all the way up. They have little problem, however, with the sitting set, the bow in Opening and Closing of Tai Chi, or Push Needle to Sea Bottom – all things that can threaten someone with a herniated disc.

People who experience progressive stenosis gradually adopt a persistently forward bent position. The malleable soft tissues running along the front of the body begin to shorten and offer increasing resistance to any sustained attempt at upright posture or lifting of the spirit. Little by little, the bent over stance becomes a problem in its own right. To look forward, it is now necessary to tip the head upward, placing a strain on the neck. The movements of the rib cage, diaphragm, lungs, heart and digestive organs, all meant to be free and easy, are impaired by the increasing forward stoop. Balance deteriorates as well.

In addition, the student may need to take rest breaks while doing the set because of increasing pain. Spinal stenosis often impairs blood flow to the nerve roots lying within the canal. Movement increases the metabolic demands on these nerves and requires that they receive more blood. Failure to deliver more blood to a working tissue results in pain.

In any given person, the pace of development of the stenosis can never be known ahead of time. Nor can its eventual severity. It may remain simply a nuisance or result in such disability that consideration is given to surgical decompression.

Our job is to work to prevent and reverse the soft tissue shortening and disturbed posture that typically develop with this disorder. While also maintaining the strength, endurance, flexibility and balance of the rest of the body.

1. Atlas of Human Anatomy, 4th Edition, 2006, Frank H. Netter, Saunders Elsevier, ISBN-13: 978-1-4160-3385-1

2. Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System, Foundations for Rehabilitation, Second Edition, 2010, Donald A. Neumann, Mosby Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-323-03989-5